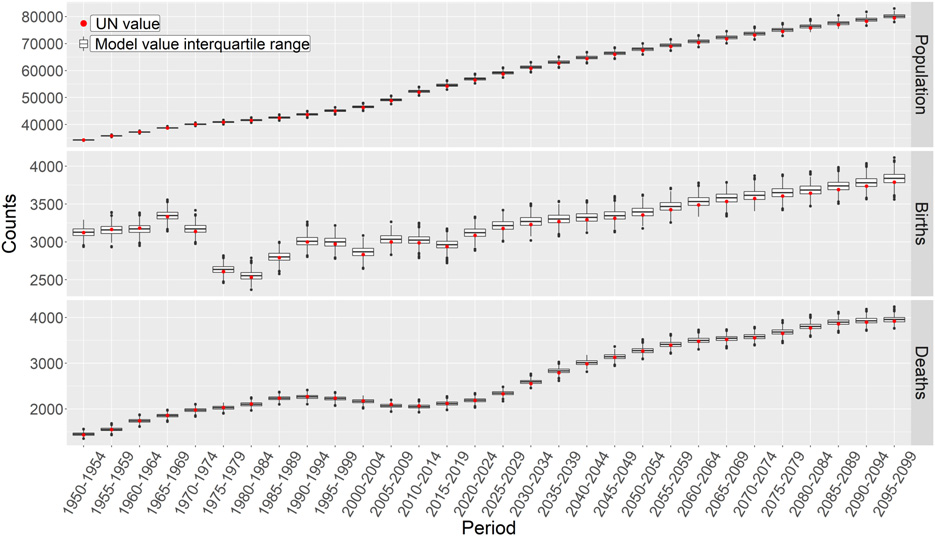

Accurate projections of population growth or decline are incredibly important for policymakers to plan for the future, making decisions about likely education, healthcare, infrastructure, and environmental needs. At present, most demographic projections such as those produced by the United Nations, rely on the cohort-component method (CCM). CCM is based on a deceptively simple equation specifying that the population at time t + 1 is equal to the population at time t, minus deaths, plus births, plus net migration (i.e. immigration minus emigration). This simple equation grows more complex but also more accurate when the population is split into cohorts, usually of 5 year periods, because then one needs to determine the probabilities of dying, giving birth, or immigrating to a new country for each 5-year cohort. The complexity increases exponentially as one tracks additional demographic factors beyond age and sex (e.g. religious or political affiliation). This paper reports on a microsimulation we created to replicate the United Nation’s CCM projections for the country of Norway. Though they require more raw computing power to run, microsimulations permit greater implementation flexibility and they also force one to specify assumptions that are often only half-conscious, yet have profound consequences on final results. As the graph above shows, our final microsimulation matched the UN CCM’s estimates and projections quite precisely, but this result required the painstaking work of surfacing these tacit assumptions and then determining how to best implement them in the microsimulation.

Here’s a link to the full article; the abstract follows below.

Social scientists generally take United Nations (UN) population projections as the baseline when considering the potential impact of any changes that could affect fertility, mortality or migration, and the UN typically does projections using the cohort-component method (CCM). The CCM technique is computationally simple and familiar to demographers. However, in order to avoid the exponential expansion of complexity as new dimensions of individual difference are added to projections, and to understand the sensitivity of projections to specific conditions, agent-based microsimulations are a better option. CCMs can mask hidden assumptions that are surfaced by the construction of microsimulations, and varying such assumptions can lead to quite different projections. CCM models are naturally the strongest form of validation for population projection microsimulations but there are many complexities and difficulties associated with matching microsimulation projections and CCM projections. Here, we describe our efforts to tackle these challenges as we validated a microsimulation for Norway by replicating a UN CCM projection. This provides guidance for other simulationists who seek to use CCMs to validate microsimulations. More importantly, it demonstrates the value of microsimulations for surfacing assumptions that frequently lie hidden, and thus unevaluated, within CCM projections.